Easy As π

π is a really important number in maths, first introduced as the value obtained by dividing the circumference of any circle by its diameter. As such π, is a fundamental constant which is intrinsic to our usual (Euclidean) model of space.

The ensuing formula C=πd (or equivalently C=2πr) emerge from this fact, relating the circumference of a circle (C) to its diameter (d) or radius (r).

Beyond this the area of a circle is said to be πr2, but in school this is often just stated as a fact with no proof given. Later, the surface area of a sphere (4πr2) and the volume of a sphere (4⁄3πr3) are also introduced, but any proof of these is not normally given until an amount of calculus has been studied (at A Level in the UK). It is however relatively straightforward to derive all these formulae with simple geometric arguments as follows:

Area of a circle

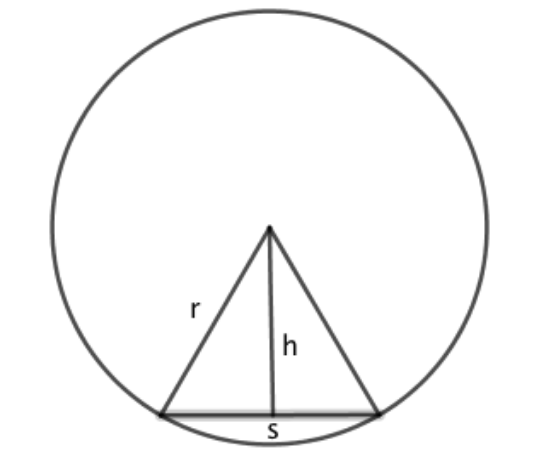

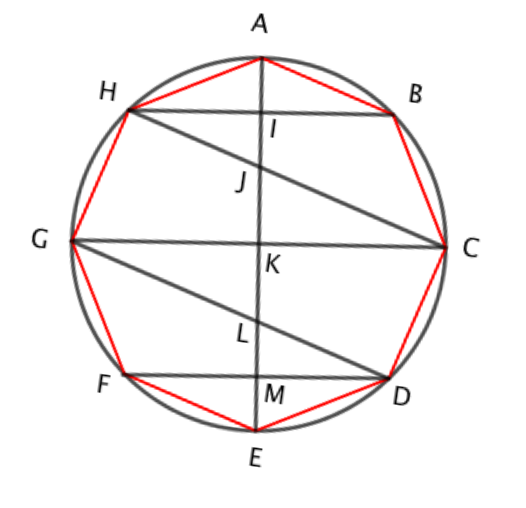

Consider a circle with an inscribed triangle joining the centre to two points on the circumference. The circle has radius r, the perpendicular height of the triangle is h and the base length of the triangle is s:

Assume we choose the angle at the top of the triangle so that a whole number of congruent triangles fit around the inside of the circle, and call this number of triangles n.

Now we can make an estimate of the circumference of the circle by adding up the base lengths of all these triangles. There are n of them, so our estimate of the circumference is ns.

We can also estimate the area of the circle. It contains n triangles, each with area 1⁄2sh, so our estimate of the circle area is 1⁄2nsh.

Both of these estimates will be less than the actual values for circumference and area of the circle as can be seen by looking at the diagram.

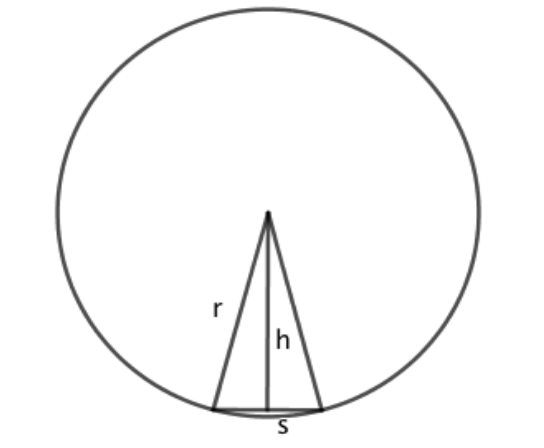

However, what if we reduced the base length of the inscribed triangle while still ensuring that an exact (greater) number of triangles still fit around the inside of the circle:

Now, n and h have increased and s has decreased. Crucially we can see from the diagram that our estimates of both the circumference and the area of the circle will be better using more triangles with shorter base length as in total they more closely fill the circle.

In fact if we keep making the base lengths of the inscribed triangles shorter then as s tends to zero (and n tends to infinity), the triangles will exactly fill our circle, so our estimates of circumference and area also become exact.

But, we know that the circumference of the circle is 2πr so this must equal our estimate, ns, as s tends to zero and n tends to infinity.

And our equation for the area is 1⁄2nsh, which also contains an ns that we know tends to 2πr as well as a h. It is clear from the diagram again that as s tends to zero, h tends to r (it becomes the length of a radius).

So the area of all the triangles, 1⁄2nsh, tends to 1⁄2 (2r) (r)= πr2, where we have replaced ns by 2πr and h by r.

And we have proved that the area of a circle with radius r is indeed equal to πr2

In the course of the above discussion a subtle and really powerful idea was rather glossed over, and it’s worth pointing out as it is fundamental to calculus, a hugely important branch of Maths. This is the point about ns tending to 2πr as the number of sides increases towards infinity and the length of each side decreases towards zero. At first sight this looks very odd indeed. How can infinity times zero give any answer at all, let alone 2πr? Well it’s to do with the fact that the number of sides and the length of each side are precisely related, so we’re not letting the side lengths and number of sides wander towards zero and infinity in any old way. For any particular side length there is a single corresponding number of sides, and as the two tend to zero and infinity while maintaining the necessary relationship, that is when the answer of 2πr arises. The important point is that it is the relationship between the two variables that defines the limit, so in a different situation the product of another two variables, one tending to zero, the other to infinity, could give a completely different answer.

Surface Area of a sphere

When finding the area of a circle we used the circumference formula, i.e. we went from a 1-d formula to a 2-d formula. Similarly, with the volume of a sphere, this is most easily found if we first know the formula for the surface area of a sphere. This time going from a 2-d formula to a 3-d formula.

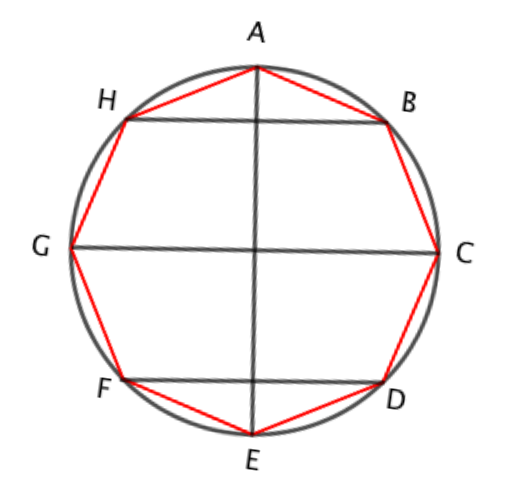

Actually, the harder part of this exercise is finding the surface area. We’ll start by considering a circle with a regular octagon inscribed within it:

If we imagine this shape being spun about the vertical line AE then we would get a sphere, inside which the straight lines would form a cone at the top and bottom (AHB and EFD), and two frustums (GHBC and FGCD). A frustum is the name of the shape made when the top of a cone is sliced off by a cut parallel to its base. As we started with a regular octagon all the sloping sides of the cones and frustums are the same length.

With this construction we can now estimate the surface area of the sphere as the curved surface area of the cones plus the curved surface area of the two frustums. Having done this we will then use the same trick that we used in finding the area of a circle. Here we will reduce the side length of our regular polygon, letting it tend to zero, at which point the surface area of the cones and frustums will be equal to the surface area of the sphere.

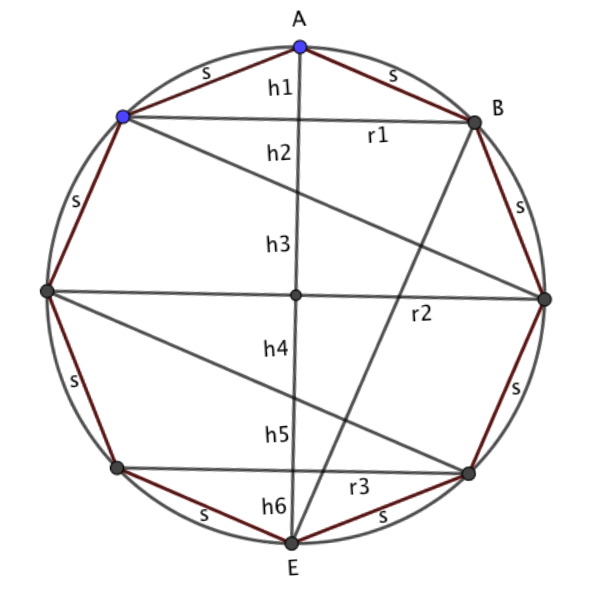

To help with this we are going to introduce a couple more lines to our diagram and then look at some of the triangles that are formed:

Let’s start by showing that triangles AIB and IHJ are congruent (angles and sides the same in both). Well, angles AIB and JIH are both right angles, and angles ABI and IHJ are alternate angles, so equal. Therefore angles IAB and IJH must also be equal. Finally, lengths IB and IH are equal since AE bisects HB and so the triangles are congruent. Note that this means lengths AI and IJ are equal.

Secondly let’s show that triangles IHJ and KJC are similar (same angles, so therefore pairs of corresponding sides are in the same ratio). Well, angles JIH and JKC are both right angles, and angles HJI and KJC are vertically opposite angles, so equal. Therefore angles KCJ and IHJ must also be equal, and the triangles are similar.

Using similar logic we can show that triangles KJC and KLG are congruent, and triangles MLD and MEF are also congruent. Additionally that triangle MLD is similar to triangle KLG.

So in summary, all of the six triangles considered are similar, with three pairs being congruent. As well as this similarity the other important fact we will use is that length AI = length IJ, length JK = length KL and length LM = length ME. And, when we add lengths AI+IJ+JK+KL+LM+ME we get the length of a diameter of the circle. We’ll call this 2r, where r is the circle’s radius.

Since we need to make use of our triangles side lengths in the following discussion here is a revised picture, showing the key lengths as opposed to the vertex labels, and with the regular polygon side length being s:

OK, so the approximation to the surface area (SA) of the sphere we can now make is the curved surface area of the cone at the top plus the curved SA of the two frustums below that pls the curved SA of the cone at the bottom.

The curved SA of a cone is πrl where r is the base radius and l is the sloping side length.

The curved SA of a frustum is π(r+R)l where r is the top radius, R is the bottom radius and l is the sloping side length.

Hence our initial approximation to the sphere SA is:

πr1s + π(r1 + r2)s + π(r2 + r3)s + πr3s = 2πs(r1 + r2 + r3)

You will have noticed that another new line appeared on the last diagram, joining point E to point B. The new triangle that is formed, AEB, is also similar to all of our other triangles. We can see this since angle EBA is the angle in a semi-circle, and so is a right angle. Also angle EAB is the same angle as IAB in the previous diagram, so triangle AEB is similar to triangle ABI and hence to all the other triangles we’ve discussed.

A key point about similar triangles is that corresponding pairs of sides are in the same ratio, so from triangles AIB, JKC, MED and AEB we can see that:

r1⁄h1 = r2⁄h3 = r3⁄h6 = EB⁄s

so:

r1 = h1EB⁄s , r2 = h3EB⁄s , r3 = h6EB⁄s

And our approximation of the sphere SA = 2πs(r1+r2+r3) = 2πs(EB⁄s)(h1+h3+h6)

And as h1=h2, h3=h4 and h5=h6, then h1+h3+h6 = 1⁄2 (h1+h2+h3+h4+h5+h6) = r

since h1+h2+h3+h4+h5+h6 = 2r

Making our circle SA estimate = 2πrEB

The final step is to think about what happens to this formula as the number of sides in our inscribed regular polygon is increased towards infinity, when the polygon eventually becomes a circle, and the rotated object becomes exactly a sphere. Well, the SA formula we ended up with, 2πrEB, actually doesn’t change as we increase the number of sides in our regular polygon, what does change though is the length EB, which gets closer and closer to the length EA, which = 2r

So in the limit, as the number of sides in the polygon tends towards infinity, the sphere SA = 2πr(2r) = 4πr2 (where we have replaced EB with 2r.)

Volume of a sphere

It will come as no surprise that our route towards the volume of a sphere is again going to use the technique of looking at a limit of the product of two quantities, one tending to zero, the other tending to infinity. To do this we’ll consider an object with many congruent 2-d faces that approximates to a sphere. How about a glitterball:

These were a common feature in discos back in the 70s and 80s. You may even have seen one more recently.

This is a useful object for us since the surface is made of many identical squares, and overall the glitterball is close in size to a sphere.

If we keep decreasing the side length of the squares the number of squares needed to cover the whole surface keeps increasing. In the limit, as the squares’ side length tends to zero and the number of squares tends to infinity, then the glitterball becomes an actual sphere, and we know the SA is then 4πr2, where r is the radius of the sphere. So if we represent the area of each square as A and the number of squares as n, then we’re saying that the limit of nA as A tends to zero and n tends to infinity is 4πr2.

Now let’s think about the volume of the glitterball. Well, if we join each corner of a square on its surface to the centre of the glitterball with a straight line the shape we get is a square based pyramid, and there are n of these in the glitterball, each with base area of A.

As the volume of a square based pyramid is 1⁄3Ah, where A is the base area and h the perpendicular height, then the volume of the glitterball is n times this, or 1⁄3nAh.

Now, we have already seen that as A tends to zero and n tends to infinity, nA tends to 4πr2. Also, as this happens, the perpendicular height of each pyramid, h, tends to r, the radius of the sphere that the glitterball becomes.

So in the limit, as the number of faces (squares) on the glitterball tends towards infinity, the sphere volume = 1⁄3nAh = 1⁄3 (4πr2)(r)= 4⁄3πr3.